CARBONIFEROUS

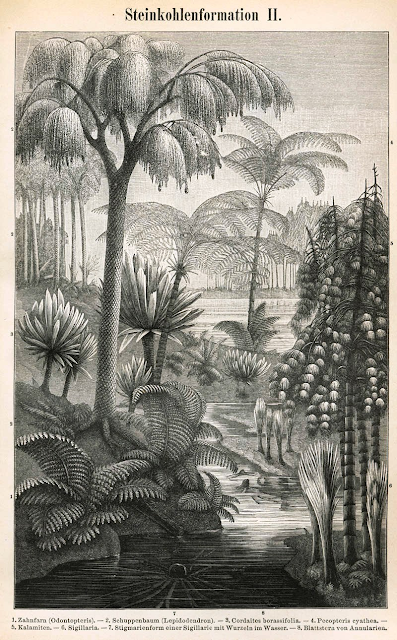

Once upon a time, in a land called Pangaea, there lived some small slimy creatures. They are of little consequence to this story, but they lived in the hot humid swamp that covered much of the land. From the swamp grew trees, and the trees were enormous as plants in this land had recently evolved the ability to produce a protein called lignin, which gave them strong trunks and enabled them to grow tall. Another advantage of lignin is that it is very tough and stable, and nothing at the time could digest it. The trees were at the top of the food chain. When they eventually died from natural causes or from falling over due to growing too big, the dead trees piled up on the ground and didn't decompose. Even in death their armour was impervious.

Whether fungi that could break down lignin at this point hadn't evolved at all or they just weren't efficient at it at the levels it was found in these prehistoric trees, and whether such fungi evolved at the end of the Carboniferous period and played a part in the trees' destruction is debated, but what is now pretty widely accepted is that the removal of carbon from the atmosphere and its accumulation in the trees caused climate change and this contributed very strongly to the eventual extinction of the trees themselves along with many other organisms in the ecosystem.

Carbon dioxide levels when these trees first evolved were around eight times as high as before the Industrial Revolution and atmospheric oxygen was 15% compared with 21% today, but at the end atmospheric oxygen was at a massive 35% and CO2 was down to the level it is today. Average temperatures dropped by 8 degrees and the land fell into an ice age. The previously warm and humid swamps were replaced by cold, arid desert as the now ill-adapted trees died out.

ANTHROPOCENE

The remains of all the trees that lived and died and piled up in the swamps never decomposed, and you probably put them in your car not too long ago. There's something ironic about the fossils of the Carboniferous rainforest being the fuel of modern anthropogenic climate change. There's also a lesson in that mankind is not unique in being an organism that drastically affects its environment. Extinction is the natural order and the vast majority of species that have ever existed are extinct, either from their own effects like humans or the trees of the Carboniferous, or from extraneous factors such as vulcanism or asteroid impacts.

Humans will, at some point in the future through whatever means, become extinct. Even if the species is able to adapt its technology to every challenge it faces, the sun will in the distant future die and the Earth will be uninhabitable, and if people manage to migrate to other worlds, eventually in the unfathomable future the Universe will collapse or all the hydrogen will be used up, etc. When humans become extinct, it will not be 'better' or 'worse' for the Earth, for other species -- it will just be 'one of those things'.

When we say, we need to halt climate change, what we are saying is, we want things to stay the same for a bit longer for the benefit of people who are alive today and some that might subsequently be born. That we don't want any given species to become extinct is more so that people can continue to experience that species firsthand or because its loss might have a detrimental effect on the ecosystem that our species benefits from, not because the endangered species cares about its extinction (few if any animals have the ability to comprehend the concept of their own mortality, let alone their extinction) or because a god/the Universe cares about that (unlikely given the vast amount of species already extinct and the vast size of the Universe). Ultimately, something else will simply evolve to fill the void. Thinking in this way is anthropocentricism (anthro = human, centric = focus).

ANTHROPOCENTRIC

Arguments for opposing climate change are anthropocentric for these reasons, just as much as are arguments for letting anthropogenic climate change run rampant like 'We need this shale gas now so that our citizens can have inexpensive electricity.'

We tend to think in anthropocentric ways in most of the things we approach, even when it superficially doesn't appear that way. It's the nature of what we are.

We are, however, the first species able to understand how we affect our environment. We are the first that is capable of doing something about it.

ANTINATALISM

A human called David Benatar wrote a book about antinatalism -- the idea that suffering is inherent to life, and therefore it is morally wrong to produce offspring. There is a great deal of sense in what Benatar said, and as someone who has had to suffer through the misery of a childhood I am someone who could not in all conscience inflict that on someone else. The logical conclusion of this idea is that the only moral course of action is for the human species to voluntarily make itself extinct by not breeding. There are a few logical and logistical problems with this.

Firstly, it would be realistically impossible to get everyone to consent to voluntary extinction. The result would be a kind of dysgenics whereby cautious and caring people largely removed themselves from the gene pool, and the next generation was made up largely of the offspring of careless irresponsible people and religious fundamentalist zealots. This would impact society and quality of life for many would likely deteriorate. A better argument can be made in terms of reducing the population, producing fewer offspring, and trying to educate people to ensure that every person who is born is deliberate and genuinely wanted by at least one parent with realistic expectations, which would hopefully mean better quality of life going forward.

Secondly, if this is only applied to humans because of their capacity to suffer greatly on psychological terms as a result of being able to conceptualise their own mortality, there are a few other species where this self-awareness hasn't been ruled out -- mainly cetaceans (whales and dolphins) and other ape species. These would need to be prevented from breeding further also. If the ability to suffer is defined very broadly, then we would need to ensure the extinction of any species with a nervous system.

Thirdly, time and space are vast on a scale people cannot comprehend, and taking this into account, the attempt even if it were successful would be utterly insignificant and meaningless. If we remove the species we deem are capable of suffering and leave plants, fungi, bacteria, and very simple animals, this will leave an unbalanced ecology that will undergo rapid evolution. The system will likely produce after billions of years have elapsed (which is nothing in evolutionary timescales) more species that are capable of suffering, and ultimately will produce something similar to humans to fill the evolutionary niche. And that species, like ours, before it can reach the position where someone like Benatar can exist and write a book, will have to inflict and have inflicted upon it atrocities such as colonialism, the Crusades and the Spanish Inquisition, invasion and slavery by Romans and Vikings, and the countless unrecorded tribal conflicts and violences that preceded them.

The same will happen if we only remove humans, or humans and other apes, for example, only much more rapidly. If we destroy our entire planet so that it cannot support any form of life, we fail to appreciate that the Universe is vast and it is extremely unlikely that complex life and concomitant suffering does not occur widely throughout it, and it is unrealistic to assume it does not simply because we cannot see it.

If we invent nihilistic deathbots and deploy them on near-light-speed vessels to eradicate life and end suffering wherever they find it, the deathbots will only become outdated because of time dilation at near lightspeed, and other organisms/deathbots will outevolve and destroy them. Life and suffering will continue with or without humans. Antinatalism is thus also anthropocentric, like the vegetarian who thinks nobody should be allowed to eat meat because farmed animals suffer from being alive, while conveniently ignoring the wild animals that go on suffering simply because that person or other people are not involved with it.

Indeed the myopic idea that the human species can effect such a cosmically profound concept as preventing suffering via its own extinction is perhaps the ultimate anthropocentric conceit.

ZERO SUM

What all this is getting to is that all species are part of a system that exists in balance. Unbalance the system, and extinctions occur and evolutionary processes drive change. This change is part of the natural order, but we may not like the effects it has on us as individuals or a species. A lesson we should learn from the Carboniferous rainforests is that it's foolish to make up dichotomies like oxygen good, carbon dioxide bad; plants v. animals; humans v. anything else; wild v. domestic. We must consider them together, as a whole system.

There's an irrational tendency when talking about extinction for people to prioritise large vertebrates over insects, plants, and fungi -- which is particularly illogical in the case of efforts expended to conserve evolutionary zombies like pandas instead of something like a fungus, plant, or insect that may have far more significance in its ecosystem. The long-term viability of any system depends on it existing in balance and conservation efforts need to focus on the habitat and the species in it as a whole. Had there been slightly more advanced fungi in the Carboniferous and animals capable of grazing the vegetation properly rather than just fish and amphibians in puddles, it might have been sustainable.

GRAZING LIVESTOCK

This was a philosophical digression, but this is intended to be the first of a series of articles about sustainable grazing management!

No comments:

Post a Comment