If your dogs enjoy agility, or you think they might, and you have some old shed doors and £20 to spend on bits from B&Q, you can make this small A-frame for home practice:

Breeder of black and brown Standard Poodles, rare breed farm animals, and alpacas near Bath.

Friday, 27 March 2015

Monday, 16 March 2015

Humorous Interlude

I will be writing a new blog post in continuation of the two about diversity breeding shortly.

In the meantime, when the weather is bad, and you try to train the dogs in the house, but it's never really the same...

Sunday, 15 March 2015

Some recent diversity studies in poodles and what they mean: Part 2

(see part 1)

Over the past few years, a study on a small part of the genome known as the DLA haplotype in poodles has been undertaken by Dr Kennedy at Manchester University. This portion of the genome is known to be involved with the immune system, and the equivalent area in other species has been found to be involved with autoimmune diseases. Thus far, 31 variations have been identified in poodles of all sizes. This test is of limited value to breeders as an estimate of diversity, partly since it concerns only one part of the whole genome, but also because the turnaround time is far too long, with some participants waiting more than a year for their result, and is therefore not suitable for aiding selection of pups to keep from a litter. More information is available here

A few years ago, Genoscoper of Finland made available a test called 'mydogdna' which analyses multiple points in the genome and generates a number for heterozygosity and a position on a graph showing how the dog fits into the population based on the results. This test usually has fast enough turnaround for litter assessment, and comes with a bonus of the neonatal encephalopathy genetic test plus some tests for colours (although the colour test for B is missing one of the alleles and is thus not reliable). For persons who have purchased a test, it's possible to see how the dog compares on an interactive graph to other poodles of different sizes and colours. In terms of answering the question 'how diverse is the breed?' Genoscoper's results would suggest perhaps more diverse than naysayers might like to think. The median heterozygosity for standard poodles is given as 31.4%. The average for all dogs (all breeds and some non-breed and mixed-breed dogs) given is 28.9%. In the technical details that are included with the 'mydogdna' test, the studies the researchers did to evaluate its effectiveness are shown. One of these studies is of a breed called the Kromfohrländer (a google image search shows it is a terrier-like dog with a rough or smooth coat). The average heterozygosity of the Kromfohrländer was 21% in the study, and to see if the test could distinguish the populations, they tested a litter of Kromfohrländer x standard poodle puppies. One can only assume the litter was an accident, or carried out for the purposes of scientific enquiry, as it is not at all apparent that the poodle would be a sensible choice to increase the genetic diversity of the terrier-like breed! The mix-breed puppies came out on the graph as having a heterozygosity of 32% -- that is, purebred standard poodles are on average only 0.6% less heterozygous in this study than a mutt of a poodle and a terrier-like dog!

More information here

The third study is being carried out as an extension of an earlier study into sebaceous adenitis by Dr Pedersen at the University of California/VGL coordinated by Natalie Green Tessier, and again involves the analysis of a number of different points across the genome. These include the DLA haplotype in the earlier study by Kennedy. Initially this study was open just to poodles suspected by pedigree analysis to have unusual genetics as it was not known how much interest it would generate or whether it would be viable as a paid test. Uptake has been very good, and it has now been developed into a usable test. Although the test is still in development, early indications are that it will be more detailed than the 'mydogdna' test and should be a more functional tool for selecting puppies and evaluating relatedness of potential breeding pairs, and promises to have a decent turnaround. Link to VGL

One of the most interesting things about the 'mydogdna' study is that it uses the genetic data to put points on a graph that shows how genetically related different dogs are to each other. Looking at the scatter plot for standard poodles and using the data from my own dogs and other dogs shared with me and made public, it's possible to see different bloodlines clustering together. The largest cluster in the diagram above made of magenta data points seems to correspond to the highly Wycliffe-influenced bloodlines. The teal outliers and cluster seem to be mostly apricot poodles, and may relate to OEA. The three unfilled data points at the bottom labelled Canen are two siblings and a cousin derived from a bloodline with relatively low influence from both OEA and Wycliffe, and the two unfilled circles above them are my dog from mixed lines including OEA, Wycliffe, and some obscure stuff, and his son.

In terms of making breeding decisions, however, the 'mydogdna' doesn't provide a great deal of detailed information. You can compare dogs to each other for potential matings and it gives you an estimate of the average heterozygosity of puppies, and this and the scatter graph are all you get, really.

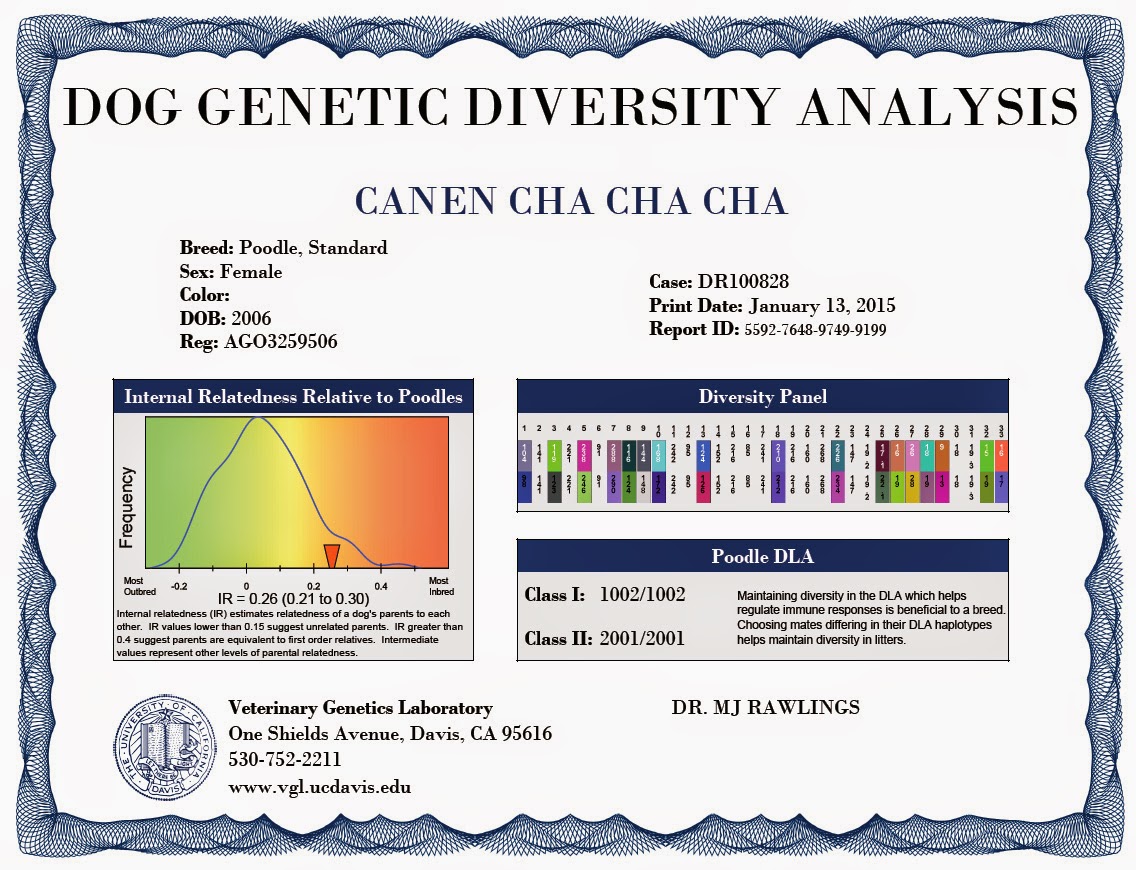

The VGL test on the other hand provides a lot of hard data in the form of a PDF that provides a measure of heterozygosity (internal relatedness) compared to other dogs of the same breed plus numbered alleles for each of the 33 genetic markers sampled, and the two DLA haplotypes. To return to the card analogy, this would be each poodle having two of each card drawn from suites containing ace-33 plus a king and queen, although it's important to remember that they are markers throughout the DNA and not the entire genome. The example below is the dam/aunt of the two siblings and cousin shown in the above 'mydogdna' plot. Her COI over 15 generations is 15%, so her higher than average IR is not unexpected, although it does not always work this way, since as explained in the previous post, COI is a probability and these tests are actual DNA markers that provide some genetic information.

And just to demonstrate that COI isn't always an accurate predictor of heterozygosity, the dog below may well have the lowest IR in the study. His 15-generation COI is 12%.

The raw data from these certificates can then be used by third-party programs to generate analyses and run mating calculations. An extremely powerful one has already been developed as an extension to the existing Standard Poodle Database, which compares dogs' results and gives an average value for potential progeny, and in addition to this it can show you how common each of the (potentially up to) 66 markers and the four DLA haplotypes your dog has are in the breed overall. VGL provides information on the numbers of different alleles (suites) for each of the markers on its website. The early results seem to suggest there is quite a lot of diversity in poodles, but that the diversity is not very evenly distributed. Most of the markers have 10+ alleles, but some have fewer, such as 16 with currently only four identified (comparable to a choice of sixteen of hearts, diamonds, clubs, or spades for each dog).

So, how can these tests be used? First of all, I should like to say, there is no one breeding plan that every breeder must use. For the breed to survive, it must be diverse as a whole, and that means it has to be bred by many diverse people who have different ideas about how to do things. That said, these tests can actually be used to support many different approaches to breeding.

Anyone can test their poodles or ask for dogs they are considering using to be tested. The VGL test is the most useful, but if you want a colour test and the NE genetic test, the Genoscoper test is probably worth doing as well. You can then compare a bitch to potential mates and use the results as part of your decision. This does not just have to be on the IR value range they are likely to produce, but can be based on rare markers, or DLA haplotypes. If your poodle has anything other than 2001 in Class II, this is unusual and worth hanging on to if possible.

After you have chosen your mating and the puppies have arrived, you can then narrow down your choice to the pups in the litter whom you think are best suited for the purposes you are breeding for, and test them and use the test results as part of your decision process on which pups to keep or to sell to particular owners. You do not have to keep the pup that is tested as having the lowest IR, or the most unusual haplotypes/markers, or use the first dog SPD recommends in terms of compatibility, if you don't like this pup or this dog, but if more people use the test and make it part of their decision, gradually this will benefit the population as a whole. Individual dogs do benefit from a low IR, but the breed as a whole and the future of individuals benefits most when much diversity is evenly distributed. It does not help the breed a lot if it is swamped by heterozygous dogs who mostly have the same two suites at each locus, and this will make heterozygosity difficult to achieve in future generations. If you have something that is unusual, IR might be less of a priority than holding on to what makes it unusual, but if you have something that genetic analysis shows to be quite typical, low IR or adding something unusual might be more relevant.

Strategies like linebreeding may not appeal to everyone and may be currently out of political favour, but historically linebreeding kept many bloodlines genetically distinct from each other and benefited the diversity of the breed taken as a whole, and this is the case with many rare breed animals today. These tests can be used to support a programme that involves linebreeding, by selecting a pup whise IR indicates it may be more heterozygous than its COI might suggest, or choosing pups most genetically different from the mainstream where the objective is to preserve a 'different' line.

Remember that when you breed two dogs, they split their hands randomly to give new hands to the puppies. Each puppy can only have one of each card from each parent. This means that if you have a bitch and you only ever keep one puppy from her and sell the rest as pets, you, and the breed, will automatically lose half of her hand. In practice due to no dog being completely heterozygous, you will lose less than this because some of her cards will be the same, but it is still important to recognise that this happens and it is a significant loss when working with bloodlines off the beaten track where there are unlikely to be more distant relatives being bred and keeping the genetics going. It is a very good idea to aim to sell some male puppies to trustworthy people who will allow them to be used responsibly at stud, as in this case there is not the worry of selling a breeding prospect bitch to someone not in a good position to be responsible for having a litter, and it will help to combat the problem of popular sires and the increasing lack of choice for those looking for someone to breed their bitch to. It is also not useful to mate a bitch again to a dog she has already had a litter to (unless the litter died, was abnormally small, or there was no suitable puppy to be kept for breeding for whatever reason). Bitches in particular who are genetically unusual should be mated to different dogs and puppies from each mating retained as potential breeding dogs.

Popular sires (dogs who are used widely for whatever reason, and are influential on the breed in subsequent generations) are usually to be avoided, and it generally makes sense to try not to use over-popular dogs or allow one's own stud dog to be overused, but where a dog is shown by these tests to be unusual, allowing a dog to be used a bit more than you might otherwise might not be such a bad thing, as it helps to rebalance diversity in the breed.

A mating that produces a low COI is usually promoted as a good thing these days, with COI being pursued by some as a breeding objective in itself, but as discussed previously, COI is just a probability. These tests help to reveal if there is genetic evidence of heterosis to support a particular low-COI mating. If there is not, there might be little to recommend a mating that was chosen primarily for its COI.

Someone wishing to import a dog where pedigree information is lacking can also use this test to find out if the dog is similar or different. Without doing the test, we don't know if the dog carries cards from the familiar suites of clubs and spades, or perhaps has a more exotic hand containing elephants and snakes.

With thanks to Natalie Green Tessier and Jane Rowden

The new SPD is available from PHR

Some recent diversity studies in poodles and what they mean: Part 1

Before getting to the crux of this matter and the studies themselves (which are going to be in the next blog post), a crash course in the principles that underpin breeding for genetic diversity, that I hope will be layman-accessible.

When we talk about diversity, we are talking about the amount of genetic variety. This variety can be within an individual, or distributed amongst many individuals forming a bloodline, a breed, or a species. In the diagram below, we can see that an individual poodle contains less genetic diversity than its breed, which contains less than the dog family (domestic dogs, wolves, dog-like animals) considered all together as a family, which contains less than the carnivora order to which dogs belong (which includes things like bears and cats) which in turn contains less than all mammals considered together and all eukaryotes.

Because calculations like COI, Wycliffe, and OEA are

predictions of heterozygosity and are highly dependent on having accurate

pedigrees, some scientific methods have been developed that look at pieces of

the dog's actual DNA and can provide a more accurate insight on how

heterozygous individual dogs are, and how similar dogs are to each other on a

genetic level. This should open up a great many more

methods of selection and breeding. The next post will explain these new tests and how they can be used.

Read part 2

When we talk about diversity, we are talking about the amount of genetic variety. This variety can be within an individual, or distributed amongst many individuals forming a bloodline, a breed, or a species. In the diagram below, we can see that an individual poodle contains less genetic diversity than its breed, which contains less than the dog family (domestic dogs, wolves, dog-like animals) considered all together as a family, which contains less than the carnivora order to which dogs belong (which includes things like bears and cats) which in turn contains less than all mammals considered together and all eukaryotes.

To make this easy to understand, try thinking of packs of cards as a genetics analogy. Cards come in packs which contain four suites and twelve individual numbers such as queen, jack, five. Let's think of the numbers as being the DNA itself (loci, or perhaps chromosomes) and the suites being alleles, i.e. versions of the same gene. Because all mammals and therefore poodles and people, have diploid DNA ('two parts'), an individual poodle can have two versions of each card. For example, it could have the king of spades and the king of clubs, or two kings of spades, but it can only have two king cards, and two of each other card.

Some of these cards we will want to be the same, because some of them will confer breed-specific attributes, and we want these genes to be consistent, otherwise our poodles or some of their offspring might end up not looking like or behaving like poodles, and would not be fit for purpose.

As another example, perhaps the four of diamonds is the card for a long, curly single coat, and the other fours confer different types of coat. All our poodles need to have two four-of-diamonds in their hand and not any other fours. For other traits, different breeders may put more value on different cards depending on their specific goals. Imagine the ace of spades is the card that causes a dog to have a black or brown-based coat and the other aces are for coat colours such as white/cream/apricot/red. As someone who enjoys blacks and browns, I like a dog who has two copies of the ace of spades, because this is a dog who can't produce cream-type colours in his offspring. A person who likes cream-type colours, however, is likely to prefer the dog who has one or both aces being something other than spades. Having two cards of the same number from different suites is what in genetic terms is called heterozygosity. Having two of a number from the same suite is conversely called homozygosity.

Other cards might have nothing to do with appearance or temperament, and be to do with the immune system. We know from scientific studies that animals with heterozygosity at the genes that control immune system function tend to be healthier, more robust, and longer-lived. So if the king, queen, and jack cards are all involved in the immune system, we ideally want to try to avoid having pairs from the same suit, and we want the breed to have as many suits as possible so we can hold on to them all to make it long-term viable.

It can sometimes happen that when a poodle splits its hand of two of each card into just one of each card to make an egg or sperm, a mistake is made and a card might be duplicated, omitted, or accidentally replaced with something else. This is what's called a random mutation. Some mutations can be harmless, for example, the three of hearts might turn into the three of diamonds. Other mutations might cause the embryo to fail to develop into a puppy, or the puppy to die soon after birth, such as an egg having no eight card, or a sperm having two kings. Some mutations may cause the gene to become nonfunctional, but have no effect when the dog gets a normal gene from the other parent. Let's imagine the six tells the dog's body how to make substances that make the dog's blood clot normally if it is injured, and that all suites are normal. Now, if a mutation in a sperm replaces the six with a 'joker' card, that is, the recessive gene for von Willebrand's disease, the puppy that is born will be healthy, because it got a normal six from its mother. However, the joker card in place of the six is now in the puppy and can be passed on, and if the puppy or a descendant of it happens to meet up with a distant relative who has also inherited the joker card, or chanced to have the same mutation, some of the puppies they produce will have two copies of the joker card and no functional 6, and will be affected by von Willebrand's disease.

Because the DNA in a dog is in effect a very large hand of

cards, the vast majority of dogs are likely to have a couple of this sort of

mutation that is harmless unless combined with one of the same. Because not all

of these mutations have tests as does the one for von Willebrand's disease, and also

because of the benefits to the immune system and general fitness that heterosis

brings, it is usually considered best to avoid breeding dogs that are

genetically very similar. At present, the genetic similarity of poodles can be

estimated by a number of tools powered by analysis of the detailed pedigrees

that are one of the great advantages of purebred dogs. Coefficient of Inbreeding (COI)

can be calculated for most breeds over a number of generations, and our breed

is blessed with a highly precise international database and accurate tool for

this in the form of the Standard Poodle Database/PHR over fifteen generations. As

the computing power accessible to most at the current time struggles to handle

calculations much over fifteen generations, it's also possible to generate

figures that allow us to evaluate the influence of two significant bottlenecks

that occurred in the breed beyond fifteen generations: these are %Wycliffe and

%OEA (Old English Apricot).

The limitation of all these methods is that they are probabilities, rather than exact

forecasts. Because of the way genetic material moves from generation to

generation, when making a new poodle, half the genetic material from each

parent is included, and the other half is not, at random. Remember in the card

analogy, an individual may only have two of each card number, that is, one from

each parent. If a completely heterozygous bitch with a deck composed of full

suites of hearts and diamonds is bred to an unrelated, completely heterozygous

dog with a deck of spades and clubs only, the deck is shuffled and split in a

way that means offspring will all have two of each card, one from each parent,

and have a hand made up equally of spades and clubs, and hearts and diamond

from each parent. But, some of the

puppies might have more clubs and hearts in their hands, and others might be

more spades and diamonds, with the result that they could either be very

similar or very different. It isn't necessarily the case that each grandparent

contributes exactly 1/4 of the genetics to the grandpuppy. The COI of a brother

to sister mating assuming no prior relatedness is 25%, but in reality this is

an averaged estimate that reflects the most likely percentage of cards that

will be the same. The siblings' potential offspring's decks could vary from

anything to 100% the same to 0% the same.

Similarly, when we say a poodle is 50% Wycliffe, what we

mean is that 50% of its pedigree traces back to five poodles used to found the

Wycliffe kennel in the 50s/60s. Although dogs who are 50% Wycliffe on average

will draw 50% of their genetic material from these poodles, an individual may

have more or less actual genetic influence because of random inheritance over a

great many generations. The more generations, the greater the degree of

inaccuracy can be.

Because a poodle has two of each card, it can carry an

effective minimum of one (two the same) and a maximum of two different versions

of each card. So the hypothetical maximum a dog can have in its hand is the

equivalent of two full suites, and the minimum is just one suite (bearing in

mind this is ignoring some cards that are always identical that confer breed

characteristics, and others that are identical and common to all dogs, all

mammals, etc.). It is beneficial for individual dogs to be heterozygous, but since a heterozygous dog is only two suites' worth of diversity, in the long term the breed is going to be in trouble if all the individuals are heterozygous but related and genetically similar, and mainly composed of only hearts and diamonds, as since cards are inherited randomly, it will be hard to ensure heterozygosity in future generations. Although there are disadvantages to the individual involved

with being very homozygous, if many individuals are very homozygous but still

different from each other, with some dogs being mostly all clubs and others

being mostly all hearts, or diamonds, or spades, or other suites we're not familiar with, this has little impact on the diversity of the breed

as a whole, as the population still has a large variety of cards of different

suites. This is why it becomes a problem when all the individuals in a breed are inbred on, say,

the famous ancestor the hearts suite came from, and heart cards become overrepresented

in all individuals of the breed, and the other suites become much rarer or perhaps

disappear entirely. When two dogs mate, if both of them have a lot of hearts cards, it makes it likely the puppies will get pairs of hearts for most of the cards in their hands.

Read part 2

Friday, 13 March 2015

Eyes

Hobson and Loki have passed their BVA eye examination. Cally's eye is still dribbling and looking a mess. We are hopefully going to see another vet soon to see if any alternatives might be feasible asides from removing it or just leaving it as it is.

The fence is finished, apart from a bit of wall at the back.

Thursday, 5 March 2015

Poodle Club of Canada article

My article on the genetics of colour in poodles has been published in the Poodle Club of Canada newsletter. I tried to keep this one fairly short and simple, although I have some more articles hopefully coming out soon in another publication that are a bit more involved. I tend to get asked quite a lot, how do I get such and such a colour, what colour should I breed my dog to, what colours will I get if I do this, what colour genetic tests should I do etc. and I also frequently come across a misunderstanding about some colour faults that can crop up occasionally in poodles being genetically 'dirty' and impossible to get rid of, which is rubbish when the faults are caused by recessive genes for which tests are widely available. So hopefully this article and the diagrams in it should be easy for people to understand and get answers to their questions from. There is also an article by Casey Carl about GDV.

They come in all these colours, but black and brown are my favourites.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)